As that time of year nears when many arts organizations host shows and sales of small artworks, it is interesting and timely to consider the historical tastes for little pieces of art. While the impending holiday season might bring exhibitions of smaller sized works to venues across the country, collectors have prized small art for centuries and the trends in modestly sized artworks have shaped art history more generally as well. Highlights from the history of art can serve as inspiration for contemporary patrons to add intimately scaled artworks to their collections.

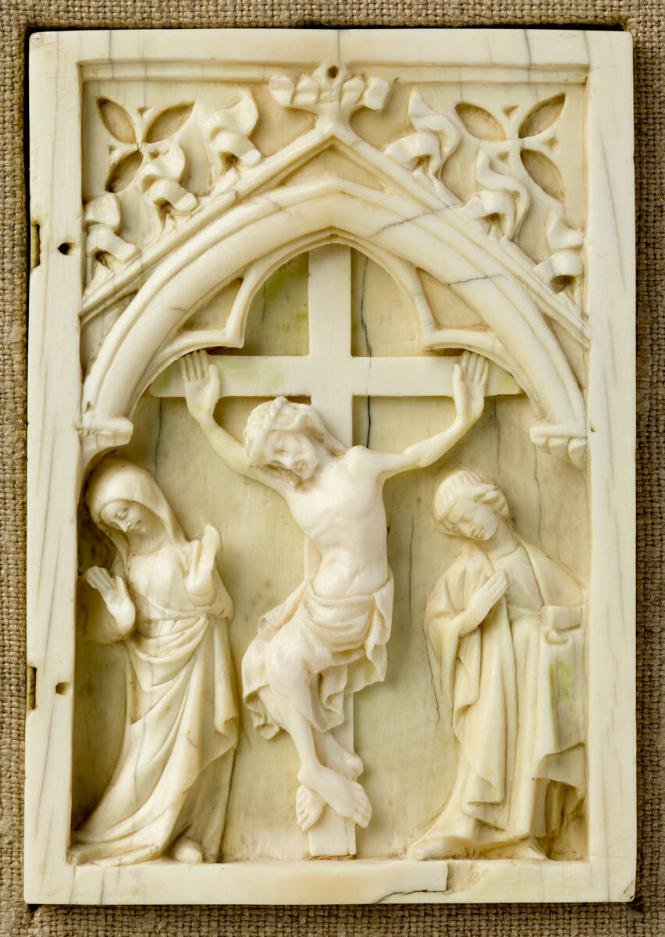

Unknown maker, Right Half of a Diptych: Crucifixion of Christ, French, c. mid1300’s, carved ivory, 10.5 x 7.3 cm (4 1/8 x 2 7/8 in.), Collection of the Worcester Art Museum

In the medieval period, art patrons were high status nobles whose lives were consequently nomadic. Travel between varying estates or to the court meant that precious works had to be mobile. Some of the most treasured artworks of the middle ages were tapestries that could be rolled and taken away. Because small objects are particularly easy to move, an entire industry sprung up around the creation of things like minute ivories that acted as tiny altars for personal Christian devotions.

France become a central location for the production of these sacred objects. Diptychs and triptychs were produced and filled with exquisitely detailed scenes from the lives of the Virgin Mary or Jesus Christ. Originally richly colored with polychrome, most medieval ivories were denuded over the centuries and now exist primarily as sculptural objects and testimonies of religious faith and artistry. For those looking to learn more about this tradition of these small ivory reliefs, the Courtauld Institute’s Gothic Ivories Project is a remarkable storehouse for research and photography.

While little ivories were exceptionally popular, the medieval world was full of small but precious things like remarkable jewelry, works of decorative arts, and tiny books of hours packed with intricate illustrations. All of these objects enable historians to get a picture of social and economic realities for those who commissioned and treasured them.

John Singleton Copley, Self-Portrait Miniature, watercolor on ivory, 1769, 1 3/8 x 1 1/8 in. (3.3 x 2.7 cm), Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Later, in the eighteenth century, another form of small art rose in stature. Items like miniature portraits and highly detailed snuff boxes came into vogue. Pieces like these were also manufactured for the upper echelon of society and were often given as love tokens or other gifts. Although small in scale, they are wonderfully illustrative and help to form a vivid picture of the social world of their time.

In a small self portrait in the collection of the Met, American artist John Singleton Copley captures his own likeness in the tiniest way. Undeterred by the small size of his ivory canvas, Copley created an image of himself that captures his fine clothes and well-coifed hair. Rosy subtleties play across his otherwise alabaster skin and the effects of light and shadow are explored in ways that are as in depth here as they might be in a larger scale work.

While miniatures like Copley’s were particularly popular in his day, there is a long tradition of their production. A detailed catalogue focused on earlier works of miniature portraiture in Europe is available via the Metropolitan Museum online.

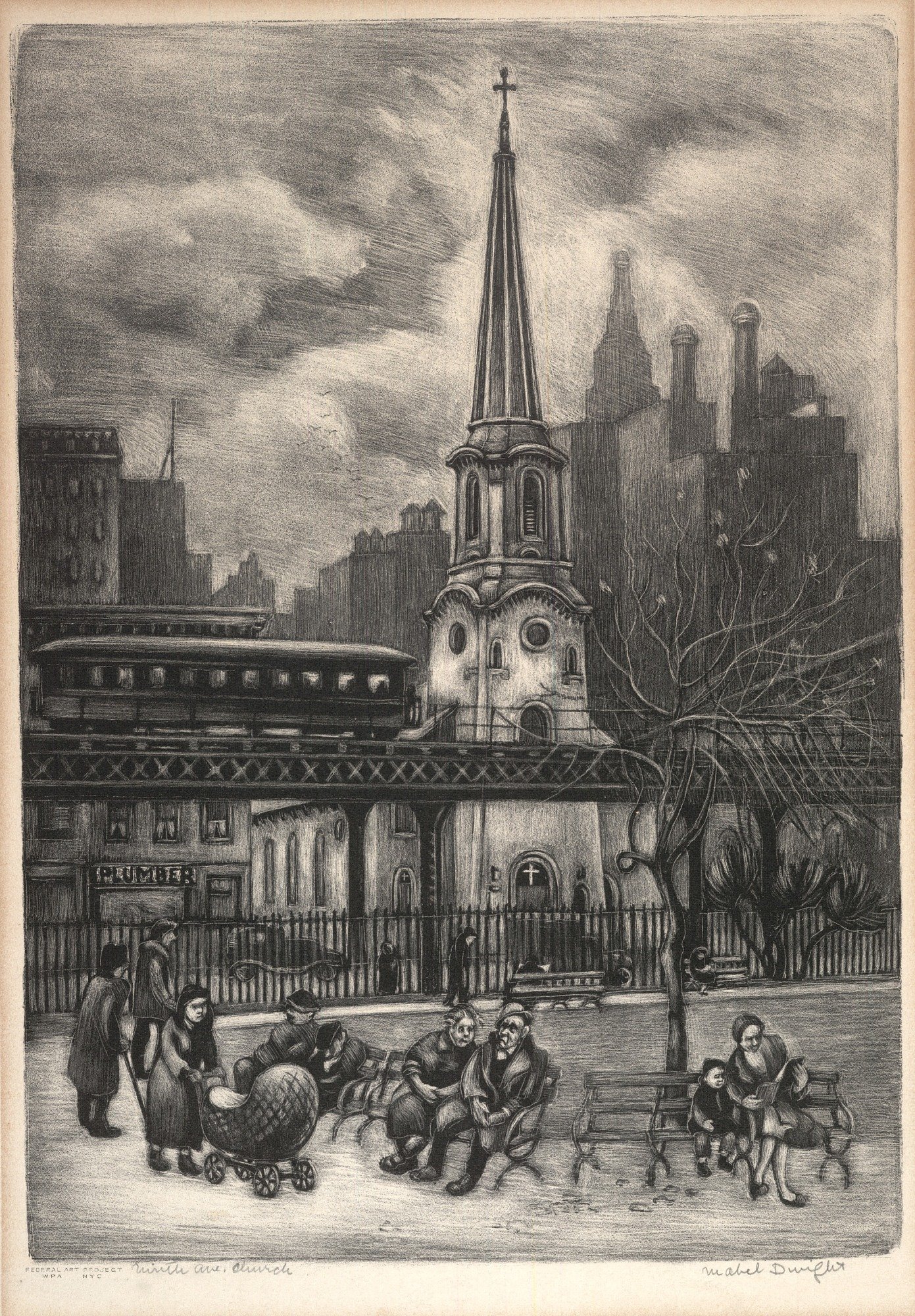

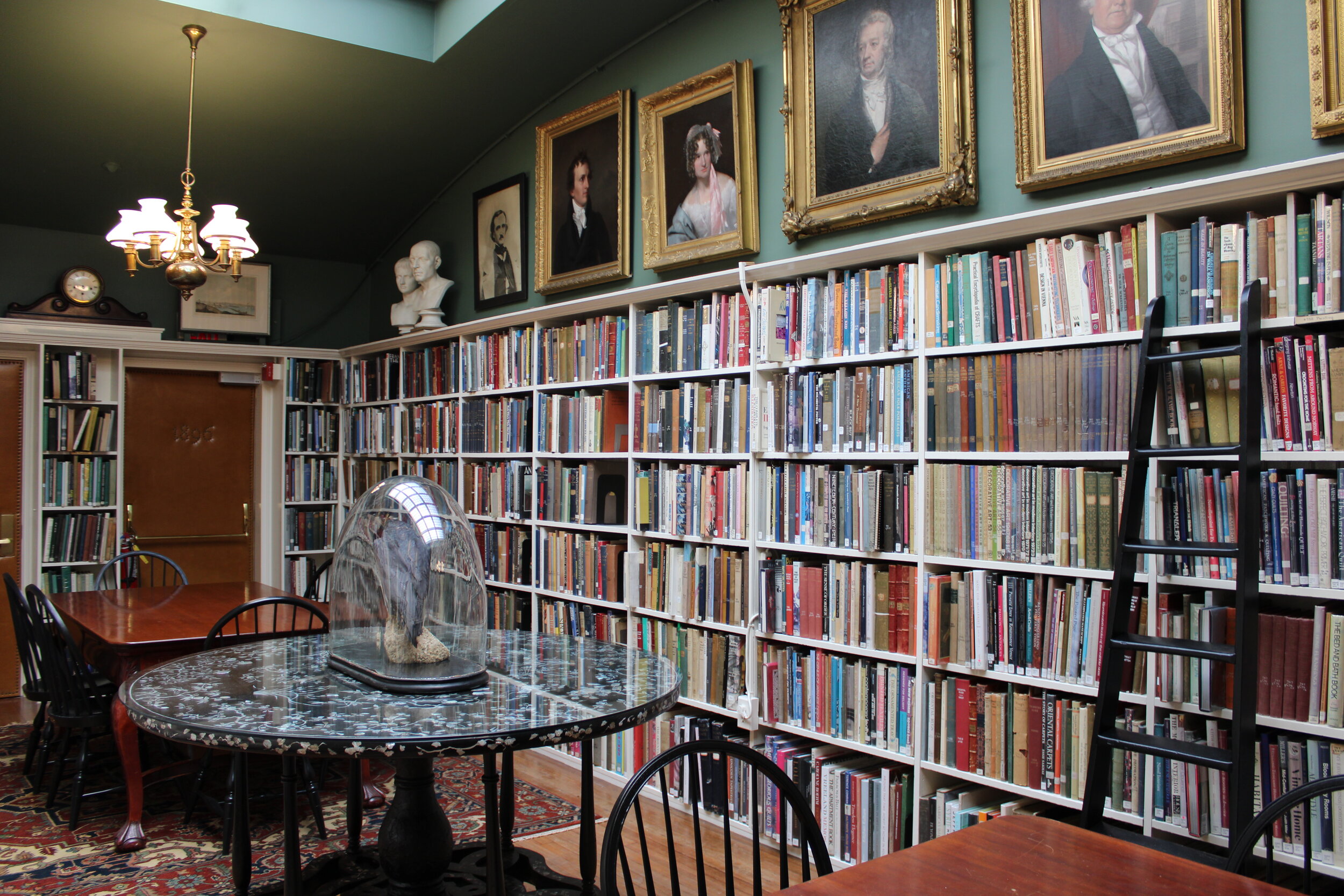

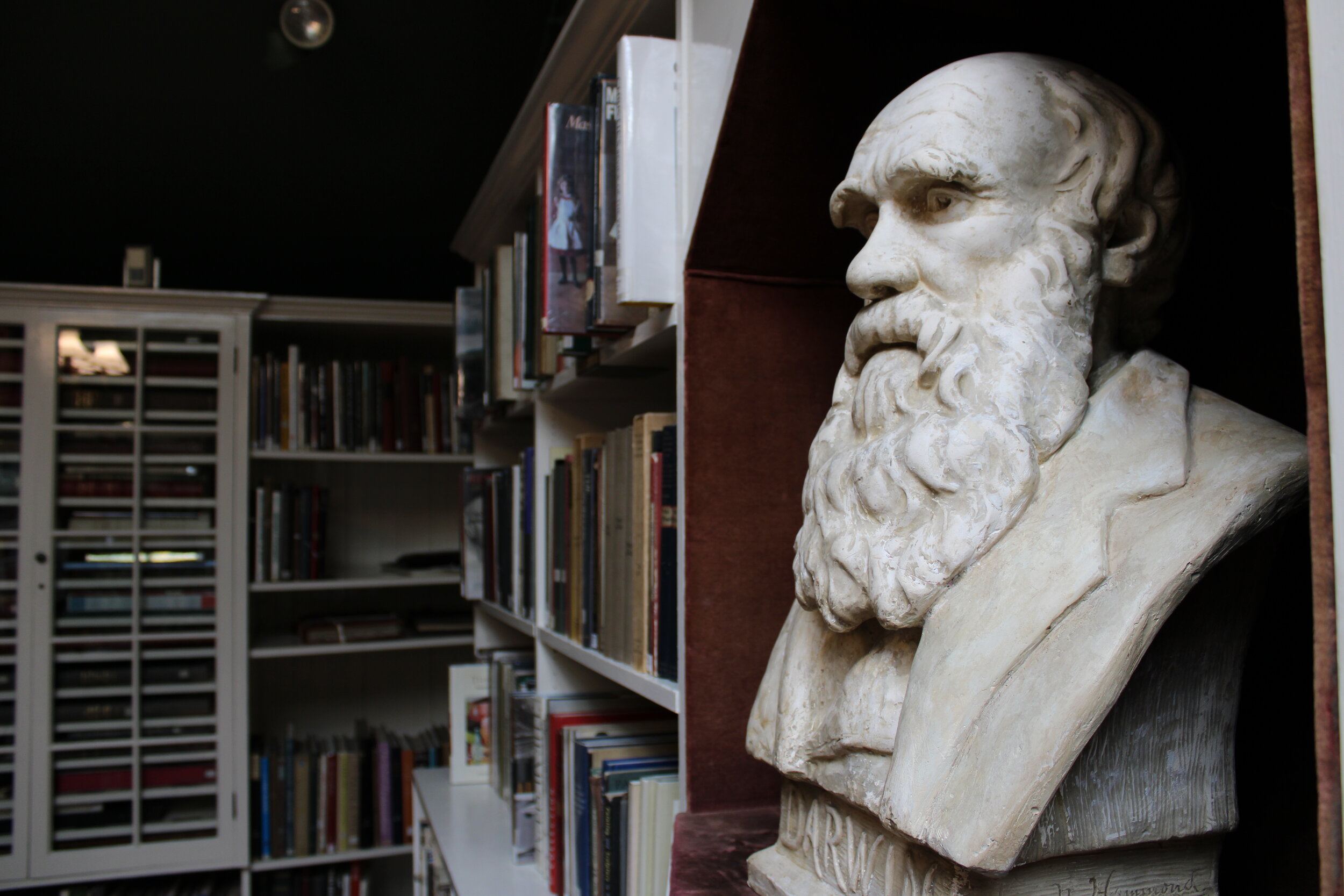

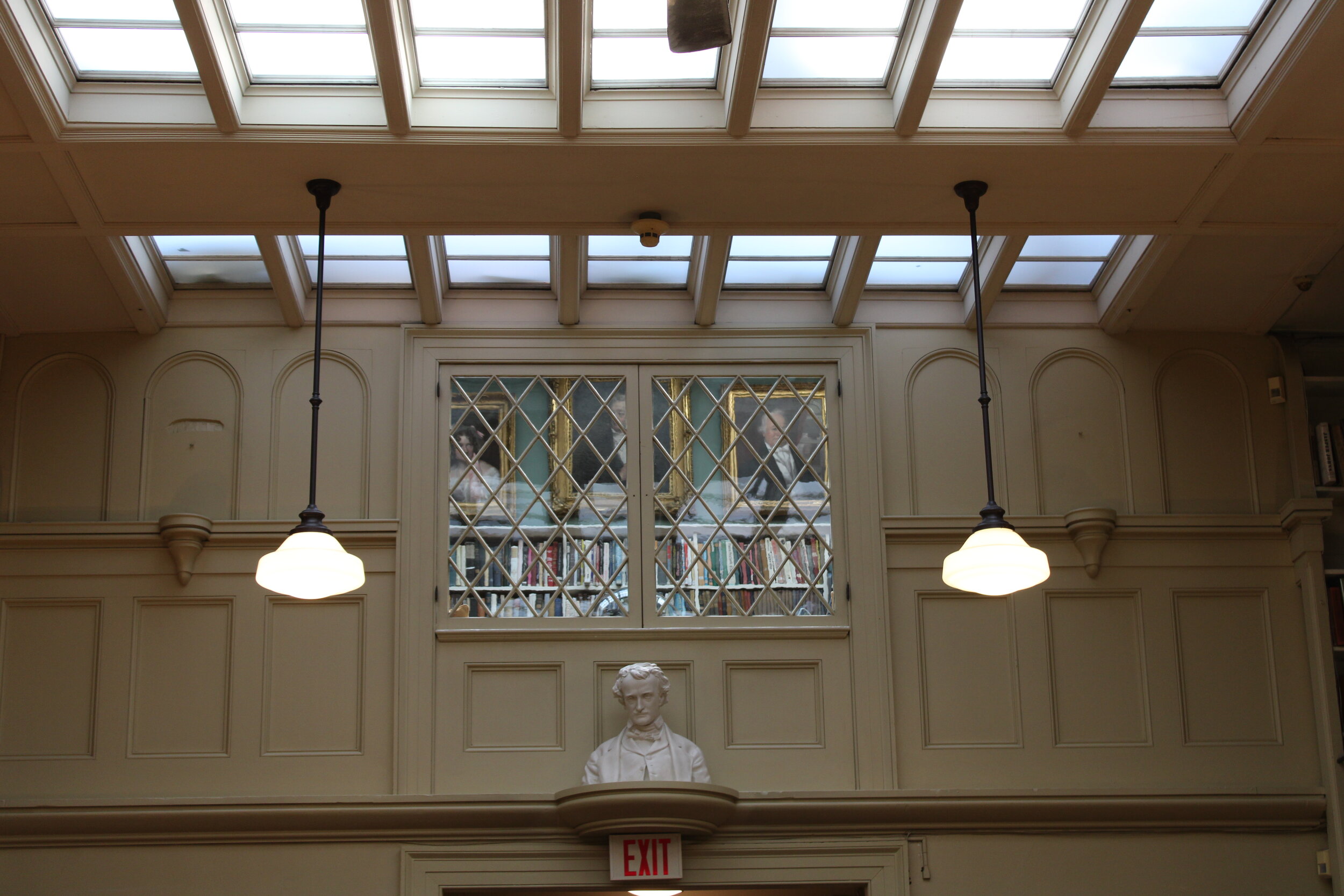

The National Gallery of Art in Washington DC has an engaging display of small panels by Georges Seurat.

Photographed by Michael Rose, summer of 2023.

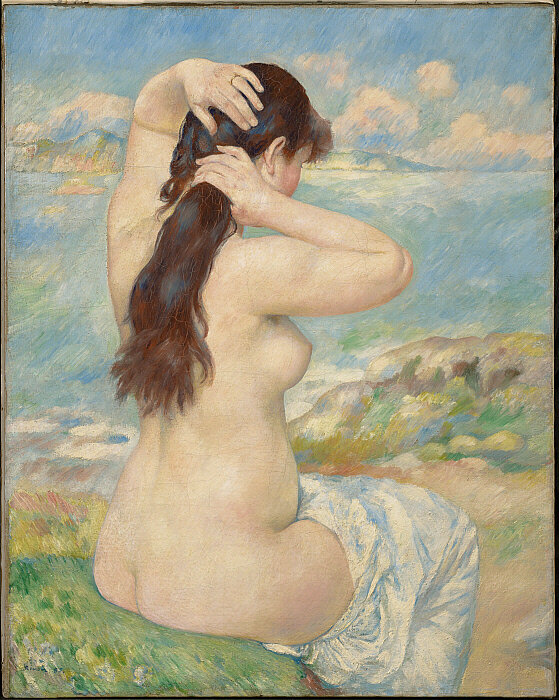

In the nineteenth century, forms of art-making shifted and became more democratized. New technologies allowed for the manufacture of novel artistic materials and artists broke out of their studios to paint en plein air. Confined by what they could carry and by what would remain stable on an easel outdoors, canvas sizes were often reduced and small panels were fodder for sketches that were as masterful and boundary-breaking as the finished works that succeeded them.

At the National Gallery in Washington DC, a case filled with panels featuring studies by the French Post-Impressionist painter Georges Seurat reads like the wall of a contemporary small works show. The wood panels in the series measure at an average of ten inches or less on their long side but are filled with the same enticing Pointillist sensibility as Seurat’s completed paintings like his famed A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of the Grand Jatte. Together, the collection illustrates the artist’s working process and the ways in which large and complex compositions could be developed in smaller bites across multiple panels.

Image of Dororhy and Herbert Vogel alongside work from their growing collection of small art in the 1960’s.

Image by Bernard Gotfryd via Wikipedia images.

Modernity has not ebbed the love for small art. The extraordinary story of collectors Herb and Dorothy Vogel is evidence of this. Throughout the mid and late twentieth century the Vogels became important collectors of some of the most significant artists of their time. Although both had blue collar jobs, they were able to amass an important collection by focusing on small works by big names including the likes of Lynda Benglis, Lois Dodd, Sol Lewitt, Robert Mangold, and Elizabeth Murray. Their sizable holdings eventually took over their modest apartment in New York and they became the subject of a PBS documentary. Much of their remarkable collection was then distributed to museums in all fifty states, making for an enormous impact in small doses.

Whether it be a devotional ivory, a tiny portrait, a nineteenth century painting, or a work of breathtaking modernism, smaller works of art have always appealed to collectors. Today, in an age of the big, the bold, and the expensive, small works exhibitions provide an outlet for artists to create work they are passionate about in a format that is often more accessible to collectors in terms of both the wall space and money required to add such a work to their holdings.

As the season of small works sales gets underway, individuals hoping to support artists in their communities might consider the proud history of collecting modest works as inspiration to buy wonderful little artworks for their own collections.