Numerous prominent arts organizations in the United States trace their roots to the turn of the century, a moment of turbulent excitement on the nation’s cultural scene. Connecticut’s New Britain Museum of American Art is one such institution. Founded in 1903, it is considered to be the first museum dedicated exclusively to the acquisition of American art. In its galleries, a wide ranging collection tells a broad story of art made in and about the United States.

While the museum has holdings that span from the Colonial period to Contemporary, some of the most compelling areas of its collection are those that chart the realities of art being made around the time of its founding. American artists in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were newly emboldened to create artworks that were in their own voice and reflective of their own concerns. In a period prior to widely accessible art education in the United States, many of these artists traveled to, and studied in, Europe and the evidence of that is displayed in New Britain’s galleries.

A contemporary painting by Titus Kaphar (far right) reflects on an earlier piece by artist Ralph Earl.

One standout sample of an American in Paris comes from Childe Hassam’s ambitious 1887 painting Le Jour du Grand Prix. In his scintillating treatment of the scene, Hassam reduces the iconic Arch de Triomphe to the edge of the canvas while dedicating the bulk of the image to the street, the trees, the people, and the atmosphere. The recipient of the 1888 Paris Salon’s Gold Medal, Le Jour du Grand Prix was also shown at the influential World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893. A highlight of New Britain’s collection, it is emblematic of where the interests of American artists laid in the late nineteenth century. It exemplifies the thrill of urban life, the drama and spectacle of a metropolis, and, of course, the cultural inspiration drawn from European travel.

Childe Hassam’s 1887 Le Jour du Grand Prix is a highlight of the museum’s late nineteenth century holdings.

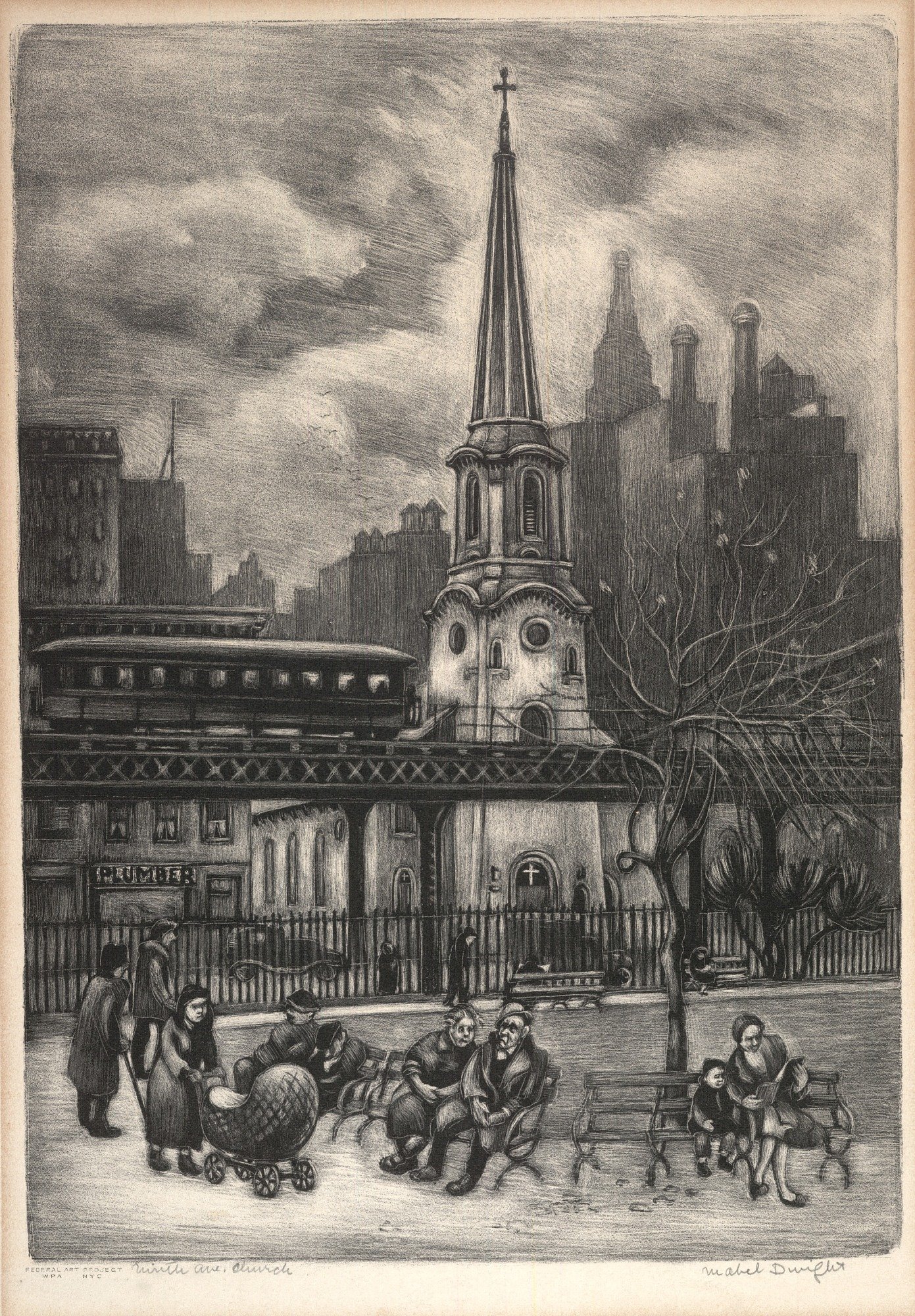

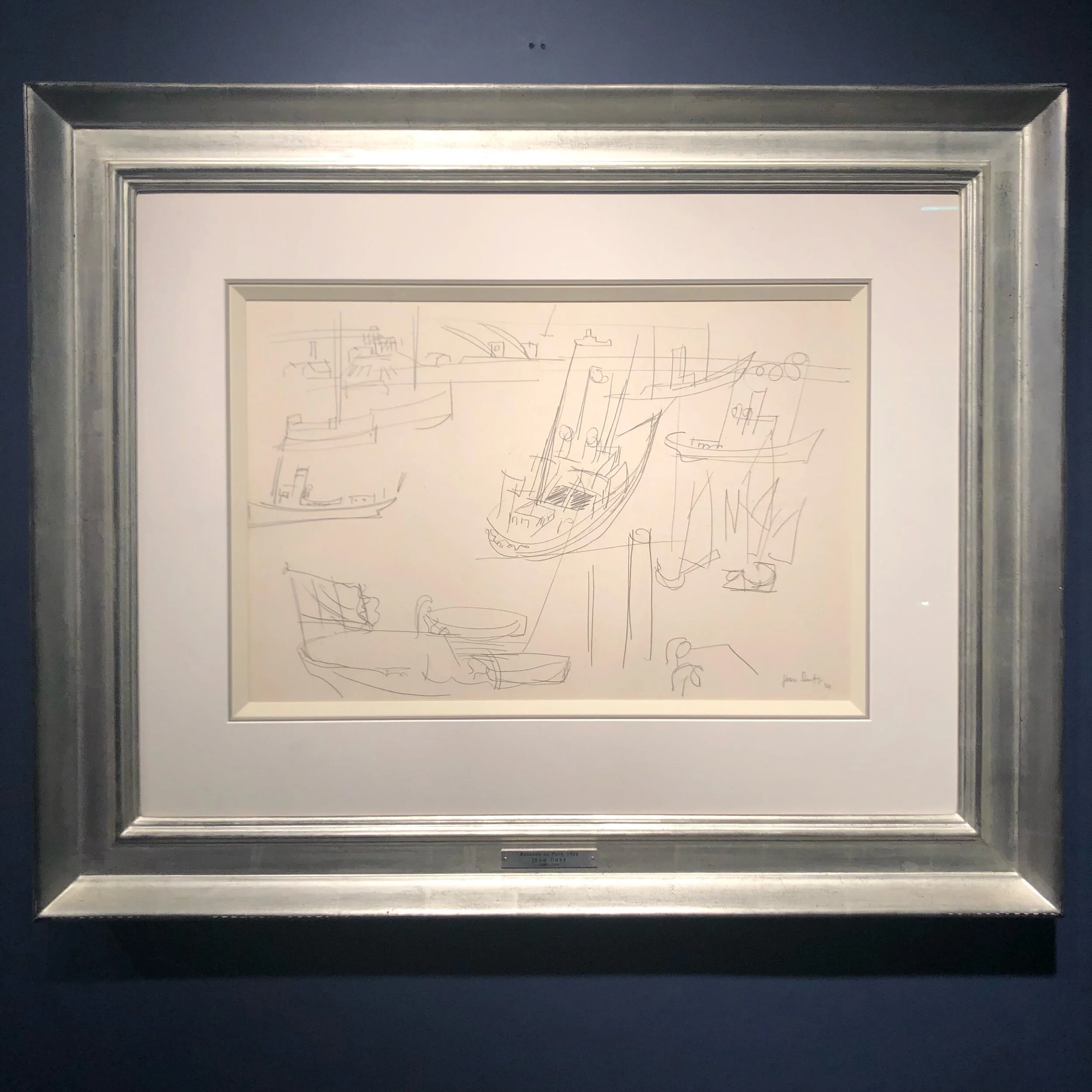

Beyond Hassam, other paintings from the likes of John Sloan, Everett Shinn, and Gifford Beal continue the trend of Americans’ passion for urban scenes and city life in the first decades of the twentieth century. As Americans poured into cities in pursuit of economic opportunities, artists turned their collective gaze toward the benefits and ills of life in places like New York. Nearby examples by Maurice Prendergrast and Rockwell Kent are more bucolic but no less engaging, and exemplify the ways in which avante-garde approaches to art-making inspired American artists. An immersive installation of murals originally created by Thomas Hart Benton for The Whitney Museum exhibits the aspirations of the Regionalist School in American art and bridges the concerns of Americans both urban and rural.

An immersive installation of Thomas Hart Benton’s Arts of Life in America mural cycle, originally designed for 10 West 8th Street in New York, the first home of The Whitney Museum.

In upstairs galleries, an exhibition on view through October 29, 2023 focuses on highlights from the Museum’s collection of Post-War and Contemporary Art. This show is broad and offers everything from explorations of Contemporary Realism to samplings from Pop Art and Abstract Expressionism. The variety is a celebration of the mixed interests of American artists in the decades after the Second World War and breaks down often monolithic art historical storylines.

An installation view of a current exhibition focused on Post-War and Contemporary Art.

Many of the museum’s sleek and well-appointed galleries date to an early 2000’s expansion project spearheaded by Boston’s Ann Beha Architects. The adjoining Landers House, which was the original venue for the museum was restored in 2021 and currently hosts an exhibition of 1970’s portraits honoring Black women who were active community leaders in the New Britain region. The entire complex hugs Walnut Hill Park. An early work of Frederick Law Olmstead, the space was designed by the nation’s preeminent landscape architect of the nineteenth century, who is best known for shaping Central Park but left a lasting impact on many public spaces.

The elegant library of the museum’s Landers House.

In addition to its permanent collection, which includes strong holdings in expected areas like the Hudson River School and American Illustration, the museum also mounts rotating exhibitions. Through September 3, 2023 it is hosting a significant show of work by photographer Walter Wick, creator of the I Spy books series, which will appeal to families. Other exhibitions on view probe topics as far afield as Shaker design and Post-War and Contemporary art.

A view from one of the museum’s current rotating exhibitions, focused on Walter Wick.

For those interested in experiencing a primer of the story of art in the United States, the New Britain Museum of American Art offers compelling opportunities to consider the legacy of visual art in the context of the American experience.

The New Britain Museum of American Art is located at 56 Lexington Street in New Britain Connecticut. It is open Wednesday - Sunday from 10am - 5pm each day and Thursdays from 10am - 8pm. Admission is $15 for adults. For more details and to plan your visit, go to www.nbmaa.org.

The New Britain Museum of American Art’s campus at 56 Lexington Street in New Britain Connecticut.