Looking back at American art in the twentieth century, some of the most valuable visual resources are those produced by printmakers. From the urban explorations of John Sloan or Edward Hopper to the more nuanced and human-focused prints of artists like Elizabeth Catlett or Sister Corita Kent, printmaking experienced something of a long golden age. Mabel Dwight is a seminal figure of the American printmaking scene, and an artist whose works are full of trenchant observations of American life. In looking at just four examples of her work, one can find insights into Dwight’s perceptive views of her time and place through the eyes of an artist.

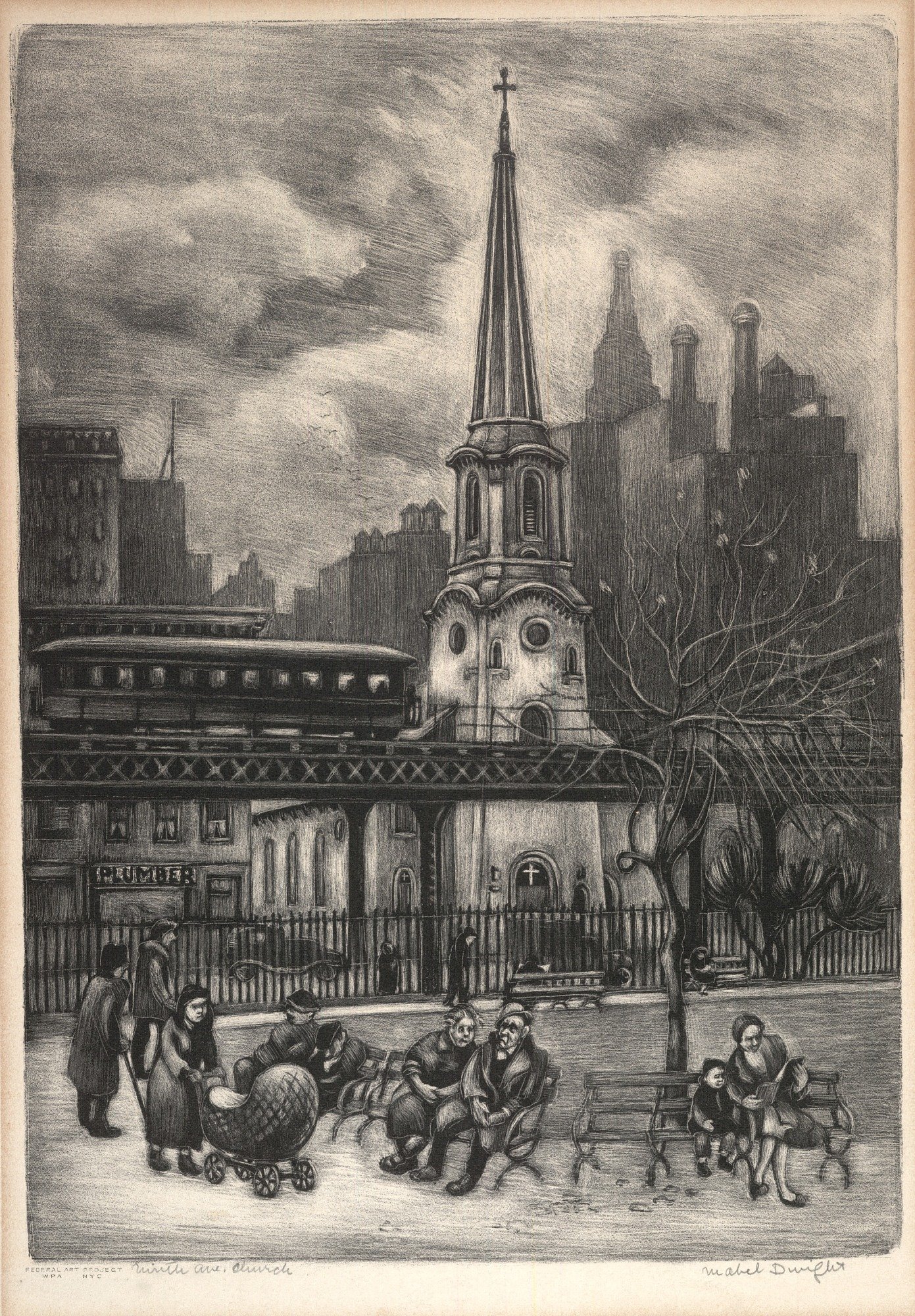

In a 1936 lithograph, titled Ninth Avenue Church, Dwight’s wry sense of humor is on display. A white church stands in the middle of the frame, with the rising city behind and a park in the foreground. What might be a bucolic scene of a New England town common is disrupted by an elevated rail line that brings a train car rattling across the center of the image, obliterating the view of the church’s charming steeple. One imagines what the scene looked like before progress brought train tracks. The image has an auditory quality too. The church bells chiming, the murmurous chatter of park goers, and the clatter that fills any urban space. Other works throughout Dwight’s production lean heavier into the funny. Quotidien images of nuns in libraries or fish in aquariums or audiences in movie theatres are transformed into delightful narrative forays.

Mabel Dwight, Ninth Ave. Church, 1936, lithograph on paper mounted on paperboard, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Transfer from the Evander Childs High School, Bronx, New York through the General Services Administration, 1975.83.46

Dwight’s sensibility for people is another through line in her prints. In her Summer Evening, a lithograph from around 1945, a group of figures gather on a street corner lit by a singular streetlamp. The light source dangles to the side of a tilting telephone pole whose wires bleed into the dark skyscape. Under the glare below, men sit on a stoop and characters chat, presumably in the cool air of early night. The image picks up on a tradition of narrative evident in other prints, perhaps most famously in Edward Hopper or Martin Lewis. Where Lewis or Hopper may have shown the scene from above, Dwight brings the viewer eye to eye with the people on the ground. For her the corner represents a nexus of community life and conversation and connectedness. Many of her artworks are ultimately about people and the lives they lead.

Mabel Dwight, Summer Evening, ca. 1945, lithograph on paper, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Bequest of Frank McClure, 1979.98.74

As much as examinations of the American scene or Americans themselves, though, Dwight was also an extremely active artist who ran in the bohemian circles shaping the nation’s art during an exciting time. In a number of images throughout her oeuvre she examines what it means to be an artist. In her Life Class, from 1931, she shows a group of students at the Whitney Studio Club drawing from a nude model. While any art student will recognize the context of the image, Dwight also captures an art historical moment. Edward Hopper and other luminaries, which Dwight counted among her peers, are present. The image is about the art of making art and it makes one want to pick up a pad and pencil.

Mabel Dwight, Life Class, lithograph, 1931, via Swann Auction Galleries

One of Dwight’s most poignant images turns from the busy excitement of a group life class to the more solitudinous feeling of the studio. Executed in the same year as Life Class, Dwight’s Night Work probes the more solitary aspects of the art practice. Possibly a Greenwich Village scene, the image captures a sort of rear window view through the grand open windows of a neighboring studio across the way. As the hazy moon shines through the clouds above, a lamp illuminates the artist’s drawing board. The scene tells both the story of bustling urban life in the early decades of the century, but also frames the artist’s experience as one that is fundamentally a lone journey in making things.

Mabel Dwight, Night Work, lithograph, 1931, via Swann Auction Galleries

Mabel Dwight’s work is well respected in print circles and held in numerous collections including those of the Smithsonian, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Museum of Modern Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and others. Her prints also appear regularly at the market and at a variety of price points. Looking at just these few examples of her work, one can appreciate Dwight’s remarkable eye and her singular contributions to the epic world of printmaking in the United States of the last century.