Rembrandt van Rijn (1606 - 1669), is known in popular memory for his emotionally charged portraits as well as for paintings of historical, mythological, and religious subjects, which exemplify the heights of Baroque drama and narrative. He was also a consummate draftsman and skilled printmaker. At the Worcester Art Museum through February 19, an impressive survey of the artist’s etchings shows off Rembrant’s talents and offers audiences an opportunity to learn about the thrilling qualities of printmaking as an artform.

Rembrandt: Etchings from the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen features some seventy works on paper by the exhibition’s titular artist as well as ancillary artworks by those who studied directly under him or found themselves in his circle. The Museum states that the exhibition is one of the largest focused on the artist’s etchings to visit the United States. A remarkable show in many respects, the exhibition is exciting for those interested in the history of the print as well as in the history of Dutch art. It also illustrates the way in which Rembrandt leveraged the power of the print to rise to the apex of popular culture in his own day.

A detail of Rembrandt’s Christ Blessing the Children and Healing the Sick, from about 1648.

One of the throughlines found in many of the pieces on view in the exhibition is Rembrandt’s keen sense of draftsmanship. His drawing skills naturally come across in his printmaking and even the subtlest of images bears this out. In some of the prints, tiny landscapes with minute figures read as larger vistas and in others the personalities of sitters are captured by Rembrandt’s distinctive portraiture. Close-looking unveils the artist’s facile hand and refined use of line and cross-hatching to create illusionistic and complex images.

Rembrandt’s Landscape with Square Tower, from 1650. A shaped plate gives this print its undulating edge.

Recurring favorites are found in multiple richly inked and dark prints. One can imagine the ways in which the candle-lit murk of the Dutch seventeenth century impacted Rembrandt’s way of making images and nocturnes or sparsely lit interiors are some of the exhibition’s most enthralling examples of what printmaking can do in the hands of a great practitioner.

A 1642 etching of Saint Jerome in a Dark Chamber shows off Rembrandt’s mastery of light and dark.

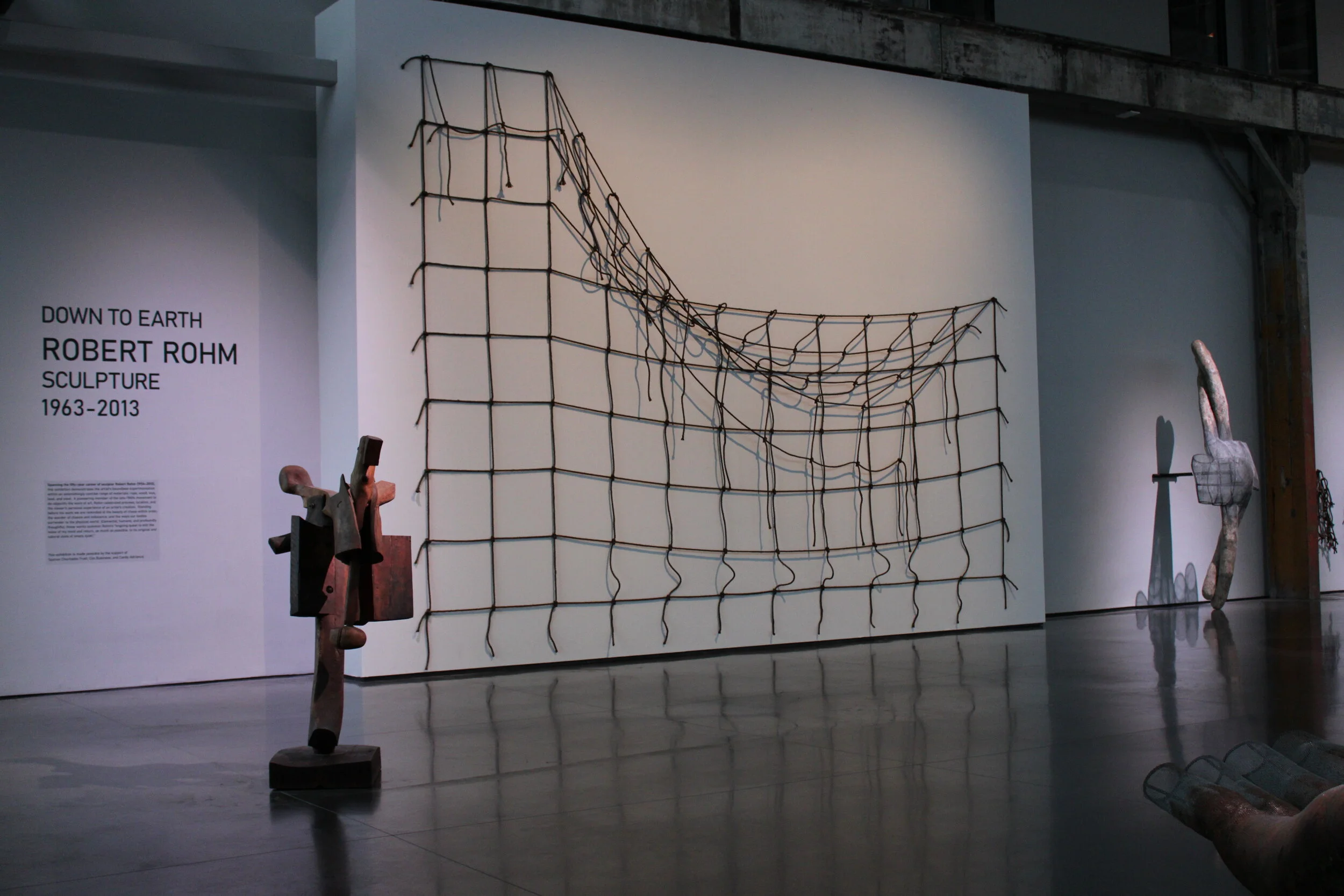

Another of the assets of this exhibition is its underlying focus on technique. With so many examples of work on display, the show also includes paper samples, explanations of tools and printmaking methods, as well as plates. A central space in the show is dedicated to the steps of making prints, which will give even a consummate print-lover things to consider. For those who are newer to etchings or to printmaking in general, this aspect of the show will provide a new appreciation for the uniqueness of prints. In their own day and now, these artworks are sometimes wrongly considered secondary to painting or sculpture.

A central component of the exhibition highlights the tools and techniques behind the prints on view.

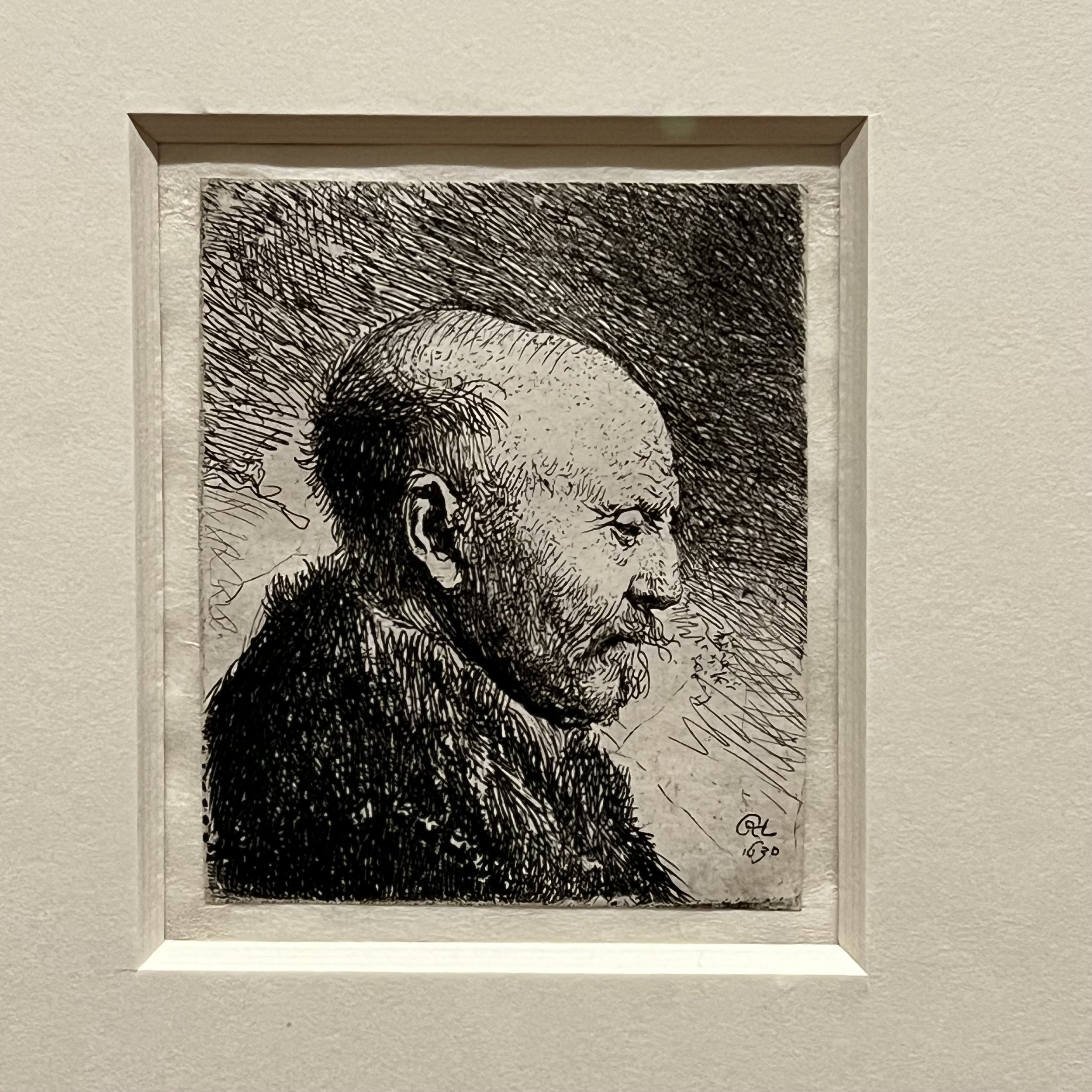

While he is rightly renowned for his skills as a painter, the sensitivity of Rembrant as a person does not lose any of its impact in the etchings presented in this show. Frail and thoroughly human bodies, full of fleshy corporealness, come up again and again in Rembrandt’s work and they are present here. Faces that bear the deep lines of laughter and tears are also present and bring viewers nose-to-nose with their long-dead counterparts. To look at these prints is to be confronted with human experience in all of its rich complexity.

An image of a Head of a Bald Man Right, dated 1630, exemplifies Rembrandt’s sensitivity to the human experience.

For those who love Rembrant, Etchings from the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen will reassure them of Rembrandt’s distinctive voice and impressive expertise as an image-maker. For those who are new to the Baroque, to printmaking, or to Rembrandt, the show has the potential to be revelatory. Either way, it is a joy to be immersed in the world of Rembrandt’s masterful etchings.

Rembrandt: Etchings from the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen is on view at the Worcester Art Museum through February 19, 2024. The Museum is located at 55 Salisbury Street in Worcester and is open Wednesdays through Sundays from 10am - 4pm. Learn more at www.worcesterart.org. See additional views of the show below.