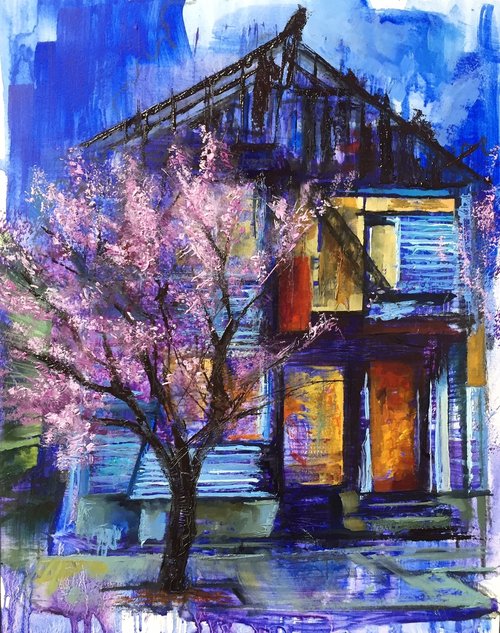

John French Sloan (1871-1951) is likely best known as one of the key members of the Ashcan School, the rough association of realist artists working primarily in New York at the turn of the century. Sloan's oeuvre is full of the gritty streetscapes typical of his movement. Some of his most well-known paintings like Dust Storm, Fifth Avenue, of 1906, Six O'Clock, Winter, of 1912, or The City from Greenwich Village, of 1922, convey a sense of the complex relationships between New Yorkers and their urban environment. From the beginning of the twentieth century into the depths of the roaring twenties, such images shape an understanding of what it meant to be a New Yorker and, more broadly, an American. Like his peer Edward Hopper, Sloan had a keen sense of the isolation and loneliness that often accompany life in a vast and impersonal metropolis. Upon closer inspection though, Sloan's body of work contains some unexpected images, including a series of nudes produced throughout his career. These images, often executed as etchings, capture solitary moments of female models in the artist's studio. They are artworks full of disparate qualities. At once sensitive and personal, they are also incredibly retrograde. They express, perhaps accidentally, the uniquely precarious relationship between artist and model, while also exhibiting the patent objectification of women which makes female nudes so problematic.

John Sloan (1871–1951), Prone Nude, etching, 1913, 3 1/4" × 6 7/16" (plate), Gift of Mrs. Harry Payne Whitney, 1926, Metropolitan Museum of Art

In an early work, Prone Nude, of 1913, Sloan references the canonical nude prototype. His model copies, with a few alterations, the infamous pose from Paul Gauguin's Spirit of The Dead Watching (Manao tupapau), a painting created twenty years earlier in Tahiti, which depicts Gauguin's terrified native wife Teha'amana laying prone on their bed. Sloan's use of the etching process flips the pose, mirroring his own subject to Gauguin's. While Teha'amana spreads her hands slightly in the earlier painting, the model in Sloan's etching half buries her face in folded arms. Both figures tightly cross their ankles and stare out chillingly at the viewer.

The gesture in Sloan's Prone Nude in the final etching also coincidentally recalls that of Francois Boucher's scandalous la Jeune Fille allongée, a portrait of Marie-Louise O'Murphy, the petite maîtresse of Louis XV. Both Gaguin's and Boucher's subjects were underage girls, bound by overtly patriarchal societies to take part in relationships that are unthinkable today. Even without the contextual baggage of Gaguin and Boucher, neither of these associations is a particularly positive one, as both are images of women presented exclusively for objectification. Sloan does not seek to correct the issues with the earlier exemplars, and instead presents a woman along the same lines as Gauguin and Boucher, devoid of agency or power in the face of the presumably male gaze. This continuity remains in Sloan's later depictions of women.

John Sloan (1871-1951), Nude Reading, 1928, etching, 5" x 7" (plate), Gift of Bernard F. Walker, Detroit Institute of Art

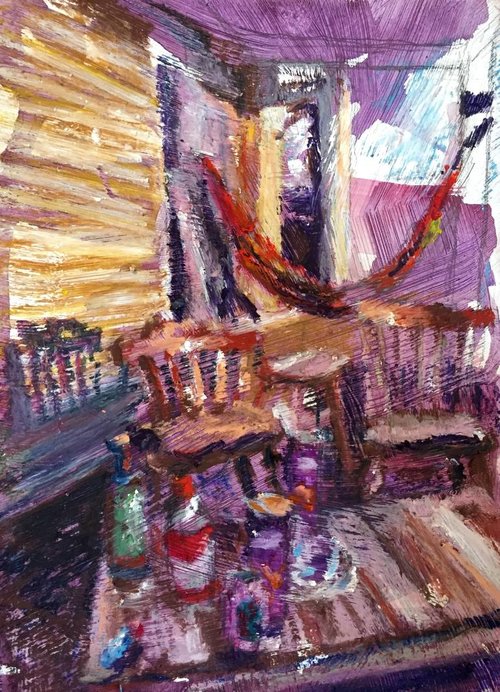

In another etching, Nude Reading, completed fifteen years after his Prone Nude, Sloan makes an image more his own. A nude model, presumably resting between poses, lounges on a bed while leisurely perusing a thick book. In the background, the artist's press is littered with materials. The scene is outwardly beautiful and meditative, but shares the same issues with Sloan's earlier Gauguin-inspired print. The woman is depicted in a one-to-one relationship with an object: the press. As the press has "a bed", the model lays on a bed. The insinuations of model as a tool of the artist, no different than a press, are obvious. The work is also a meditation on the process of creating the etching. The subject is present and so is the press on which this very print was likely created. In addition to revealing aspects of the artist's creative process though, it also presents a decidedly traditional view of the model's role in the creation of such work, as a passive object.

John Sloan (1871-1951), Nude and Etching Press, etching, 1931, plate: 4 15/16" × 3 15/16" sheet: 12 11/16" × 9 5/8", Gift of Ernest Shapiro and Family 1995, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

In 1931, Sloan revisits the model and press motif in Nude and Etching Press. This time the figure stands with some discernible confidence next to the artist's press. The lithe arms of the anonymous woman replicate the outstretched "arms" of the press. The curvilinear qualities of the press's legs mirror the shapely legs of the model. Again, Sloan presents a woman one-to-one with an object. Neither this figure, nor the Nude Reading, interact with the press at all. Both merely pose in front of the it, and are nearly as still as Sloan's early Prone Nude. Both images elevate and personify the press, while simultaneously diminishing the humanity of the model. This piece, like the earlier nude paired with the press, is an apparent study of the artist's process. Tacked up haphazardly on the wall above the press are nearly a dozen nudes. Perhaps the model here is stretching between more formal poses, with the knowledge that her image too will be added to this collection.

John Sloan (1871-1951), Nude and Arch, etching and engraving, 1933, 7" x 5", on offer at Swann Auction Galleries March 13, 2018 19th Century Prints and Drawings Auction (Est. $1,500-$2,500) This work was Unsold.

Another Sloan nude appeared in Swann Auction Galleries' recent Prints and Drawings sale on March 13. The work, which went unsold, comes two years after the Nude and Etching Press, and features a model seated uncomfortably on a cushion in front of a window overlooking Greenwich Village. Stanford White's Beaux Art Washington Square Arch stands in bright sunlight in the eponymously named park, framed in the window behind the model. Scenes of city life are also evident, as cars can be seen through and around the arch. Windows of the apartment blocks abutting Washington Square Park form a further backdrop, and an added urbanity. The wrought iron railing and arch give the scene a vaguely Parisian air, imbued with the distinctly Bohemian feeling of the Village in the twenties and thirties. The model here is much more engaged with the viewer than her predecessors, staring out at us wanly. Still though, she is presented one-to-one with an object: the arch. The classical associations of arch and nude are quickly evident. Here though they are updated to New York in 1933, the Città Eterna of the New World.

In all of these pieces the aesthetic values of the Ashcan School are laid out in the medium of the etching. Richly and darkly inked, each plate is thick with crosshatching. Even the smooth-skinned model is criss crossed with descriptive lines. Sloan clearly revels in the textural and linear qualities inherent to the printmaking process and tends to fill the whole field of the plate with lines, independent of their necessity to express value or space. This technique results in prints that are as course as his paintings of metropolitan life. In terms of execution, these images hold together with a stylistic coherence that spans much of Sloan's career.

The problems present in Sloan's portrayals of his models are rather obvious to contemporary onlookers, if not unusual in his own day. The use of models to hone hand-eye coordination and express supposedly universal or eternal artistic values was a time honored tradition and would have been a key point in Sloan's education at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. It is difficult, though, to reconcile the avant-garde nature of so much of Sloan's oeuvre with the way in which he envisaged nude women. He was a leader of a liberal art movement, an avowed communist, and a rebellious spirit, yet his depictions of women are ensnared by many of the trappings shared by more conservative artists.

While they do offer access to usually unseen moments in the artist's studio and creative practice, these nudes also engage in typically misogynistic portrayals of female bodies. They can and should be appreciated for their craftsmanship, for their ability to show Sloan's process, and for their storytelling capability. But they are surprisingly out of step with the values evident in Sloan's life and in his broader body of work.